Elaine Qiao

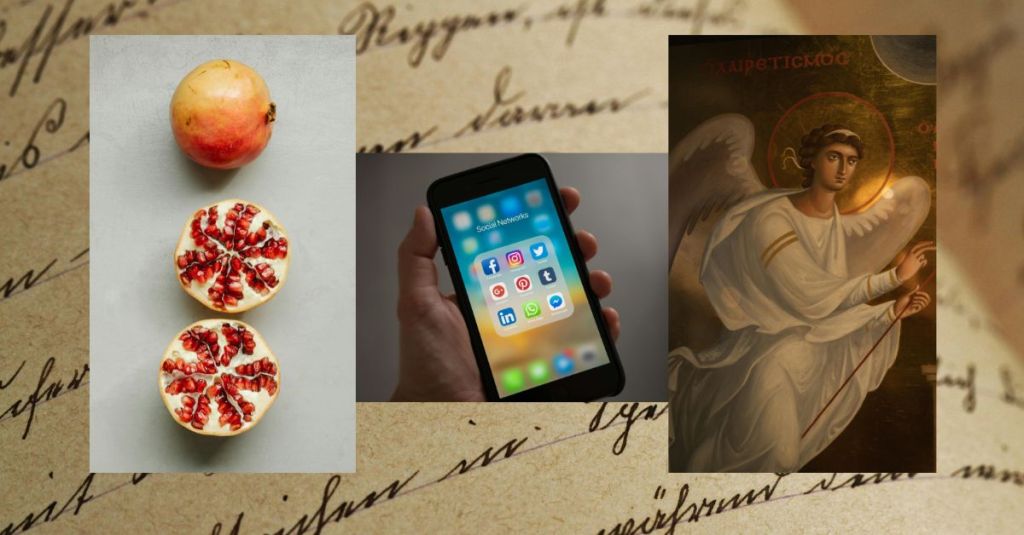

Cannibalism as a metaphor for love. There are claw marks in everything I’ve ever let go of. Persephone’s pomegranate.

Over and over, I see these quotes on my TikTok For You Page, layered over either an aesthetic curation of images or an overacted recording of a girl moved to tears. The effect of these lines has been immediate, making it into poetry, podcasts, and song lyrics alike that resonate with millions. Yet simultaneously to all the likes and reposts, there’s been ongoing backlash toward this content. TikTok critics attribute this new online literary trend of mass-produced sentiments on love and womanhood to a resurgence of Tumblr and feminine pseudointellectual bandwagoners. To them, these oversaturated themes are not only uninspired but showcase an inability of a generation of women to think for themselves and collate their own repertoire of references.

I must admit, past the initial relatability of mass-reposted literary clichés, I don’t find much substance behind the words. Upon inspection, these quotes do seem to grant marketability above all else. The language is beautiful, drawing on common themes of intense love, fear of abandonment, and loss of innocence, its literary facade maintaining just enough distance from the mainstream to attract those seeking depth and taste. The pomegranate, for example, with all its difficulty to eat, has become a symbol of the effort it takes to know and love someone despite their shortcomings. Though perhaps originally well-articulated and rooted in classical literary tradition, writing under these “Tumblr” themes seems to have morphed into trendy pseudoliterature.

Donna Haraway, who originated the feminist gender theory of the cyborg, believes that “[g]rammar,” and perhaps the regulations of the literary sphere as a whole, “is politics by other means” [1]. While mildly irritating to come across on my algorithm, these TikTok recitations are a reminder of the weight of linguistic form. In an era of rising conservatism, isolation, and the male loneliness epidemic, accusing a literary trend so clearly fueled by young women as being shallow feels like bad form. Moreover, accessibility is central to the issue. Though TikTok might be overcommercializing the literary space, it’s also providing an entry point for many who may find themselves otherwise excluded. To expect highbrow lyricism from short-form social media content isn’t only unfair—it’s pretentious.

Is it enough to say “It’s not that deep”? Can we really write off the emotional significance of this ongoing literary trend for so many women as inconsequential or lacking substance?

Though perhaps originally well-articulated and rooted in classical literary tradition, writing under these “Tumblr” themes seems to have morphed into trendy pseudoliterature.

These TikToks have struck the hearts of numerous women, a phenomenon that may have psychoanalytic backing. Cognitive style was central to the socialization of gender in earlier conceptions of feminist standpoint theory—a school of thought exploring how marginalized identities hold more nuanced and complete understandings of social reality. Standpoint theorists such as Nancy Hartsock, Hilary Rose, and Dorothy Smith apply concepts within the related, though methodologically distinct field of object relations theory, which explores how early parental relationships shape future personality and interactions. Hartsock, Rose, and Smith argue that men form masculine identities through distance from the mother, a mechanism of separation [2, 3, 4]. By contrast, women are believed to form feminine identities through relating to their mothers, allowing for a blurred relationship between the self and the other.

It’s important to note the imperfections in this argument: the overemphasis of the mother-child dyad, enforcement of a gender binary, and exclusion of other structural influences in identity. At the same time, this theory provides a compelling angle into the socialization of gender that might inform an understanding of this literary moment.

Given this framework, perhaps this ongoing TikTok trend has created a politics of care, a way for a generation of young women to relate to one another and come to terms with a pervasive intensity of feeling and sense of neglect. When I was in the worst stage of a breakup, I came across a reel of a girl around my age. I watched her cry to the camera that there weren’t any scratches on her despite everything she’s ever loved being ridden with claw marks, allowing me to indulge in some much-needed melodrama.

At the same time, to assign further significance to this wave of TikTok literature feels like failing authors whose writing and research is more nuanced, intersectional, and comprehensive. While the impact of this trend of modernized myths and lovelorn platitudes shouldn’t be understated, the work also lacks the breadth of discourse to merit the intellectual depth that some social media users may insist on. It is precisely this claim to the niche that frustrates me. This kind of writing isn’t meaningless, yet it regurgitates the same concepts over and over in increasingly manufactured form.

I’m tempted here to make an argument on how these themes, disproportionately centering on romance and heartbreak, push forward a reductive kind of content for women to fixate on and digest that may be unproductive. Yet repetitive themes are not new to this generation of writing. We’ve been musing over the same recycled ideas of love, mortality, grief, and coming of age for centuries. There are a million versions of the epic. It’s the scale at which these ideas are being replicated on social media platforms that pose an issue—the same lines, copied and pasted on countless anonymous poetry accounts or reiterated by spoken-word influencers.

This kind of writing isn’t meaningless, yet it regurgitates the same concepts over and over in increasingly manufactured form.

Melissa Febos, memoirist of Whip Smart: The True Story of a Secret Life, advocates in a Poets & Writers Magazine article for personal writing: “That these topics of the body, the emotional interior, the domestic, the sexual, the relational are all undervalued in intellectual literary terms, and are all associated with the female spheres of being is not a coincidence,” she articulates [5]. For Febos, the distinction between emotional, assigned as female, and intellectual, assigned as male, is a political tool within the literary space.

To Febos, writing about trauma is subversive. “The stigma of victimhood is a timeworn tool of oppressive powers to gaslight the people they subjugate” she says. By discrediting these writers as dramatic, whiny, or “beating a dead horse,” the white masculine hegemony within the literary sphere silences marginalized authors in their disempowerment. While this may, at first read, corroborate the value of Tumblr literature, Febos’s argument might, in fact, point out this monotonous literary trend’s fatal flaw.

In Dialectic of Enlightenment, Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer discuss the culture industry—or capitalistic mass-manufacturing of cultural products for profit. “Films, radio and magazines make up a system which is uniform as a whole and in every part. Even the aesthetic activities of political opposites are one in their enthusiastic obedience to the rhythm of the iron system,” Adorno and Horkheimer claim [6]. This TikTok trend, then, and perhaps art on social media as a whole, has become a new avenue for profit motive, performing and monetizing in a uniformity detrimental to artistic individuality.

Just creating space for more feminine narratives isn’t enough.

With the influx of content that is commercially replicated to this degree, the movement has lost any semblance of personal touch. The writing lacks depth not because the subject matter is overdone but because the writers aren’t going beyond their initial connection to the existing work. Sure, we’ve all been around the bend of womanhood, but we don’t have any real idea how to convey what it was like walking the path. Without that expression, there’s no difference in weight or tenor in supposedly distinct bodies of work. Maybe that’s why the content feels so shallow to me. Just creating space for more feminine narratives isn’t enough. The labor has to be done to cultivate stories about the feminine experience that hold enough specificity to be universal. Otherwise, it all feels like one big cash grab.

I, personally, will be scrolling past when I see another TikTok on the epiphanies that come with peeling a pomegranate. So much of the value in the online literary space is the widely accessible audience and opportunity for connection. Overendorsing a movement of copy and paste fails the charms and challenges of writing for social media and churns out subpar products to be sold. But I also don’t feel it’s my place to police what another woman finds beautiful. When the internet surges and recedes into a new wave of literature, perhaps it will be me leaving claw marks in this era of online writing that has sustained and repelled so many.

References:

- Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002).

- Haraway, Donna. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge, 1991.

- Nancy Hartsock. “The Feminist Standpoint: Developing the Ground for a Specifically Feminist Historical Materialism” (Indiana University Press, 1987).

- Hilary Rose. “Hand, Brain, and Heart: A Feminist Epistemology for the Natural Sciences” (University of Chicago Press, 1987).

- Elizabeth Anderson. “Feminist Epistemology and Philosophy of Science.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman, (Summer 2024).

- Melissa Febos. “The Heart-Work: Writing About Trauma as a Subversive Act,” Poets & Writers, December 14, 2016. https://www.pw.org/content/the_heartwork_writing_about_trauma_as_a_subversive_act?cmnt_all=1

Leave a comment