Giselle Lipsky

I couldn’t walk away from her. Once that thought had firmly planted itself in my mind, I could not seem to shake it. There I stood, my feet glued to the floor and my knees locked in assuredness. The long minutes passed as I stood there finding comfort in the bond we shared. I also realized that if I stayed there, watching over her in half protection and half solidarity, not only would neither of us be alone, she would never have to die.

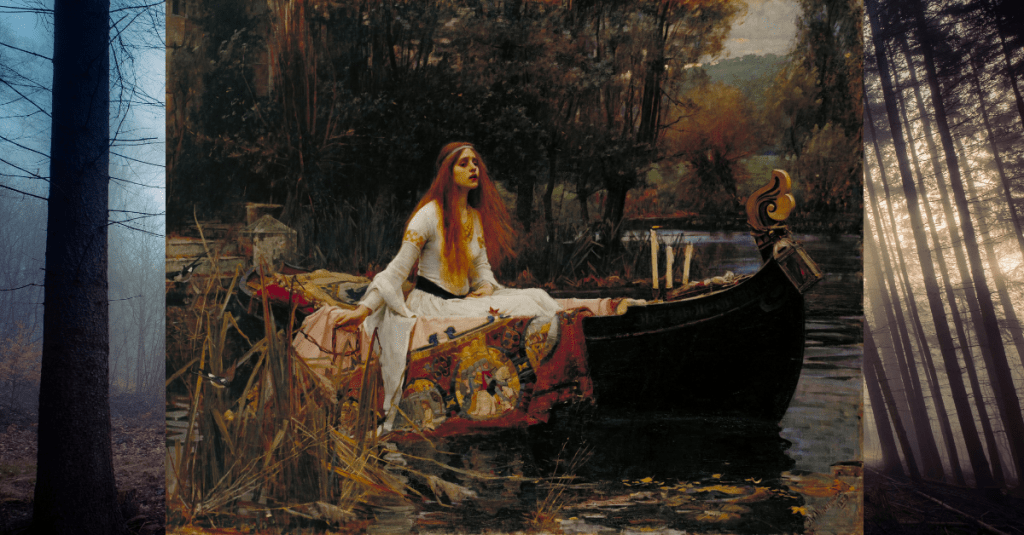

She is the Lady of Shalott, depicted in revelatory translucence by the painter John William Waterhouse in his 1888 painting of the same name. In the painting, a young woman sits in a boat carrying her off into a misty river scene. She looks heartbroken, contemplative, and exudes a yearning melancholy. As I stood in front of her at the Tate Britain, I felt imbued with the power to freeze time, both hers and my own. As long as I kept my watchful eyes on the scene, she would never let the chain drop and the boat would never carry her down the river to her death. I, in return, could postpone the rest of the day I’d spend alone in a new, overwhelming city.

This poetically visual feast is the ideal source material for Waterhouse, himself a member of the equally poetic and romanticized Pre-Raphaelite artistic movement.

The painting depicts the climactic turning point in Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s 1832 lyrical ballad of the same name, which recounts the life and death of the Arthurian heroine Elaine of Astolat, more well-known under her nameless moniker. Tennyson relied upon the 13th-century Italian short prose novella, “Donna di Scalotta,” along with Sir Thomas Malory’s 15th-century prose compilation, “Le Morte d’Arthur”—which canonized much of the legend of King Arthur and his knights for Tennyson’s return to the story in “Lancelot and Elaine.” Prior to Malory’s collection, Camelot had existed as a fixture of both French and British folklore, scattered in inconsistency. As a result of those essential works, though, a new genre of “Arthurian romance” spread through Europe, relying mostly on the French and Italian origins over the Britannic and Celtic myths.

By the time Tennyson joined the canon, the collection of stories had coalesced into what we now consider the folklore of Camelot, and it was time for the reigning Poet Laureate to put his own spin on the magical world. He would go on to follow “The Lady of Shalott,” with The Idylls of the King, a longer, complete retelling of the myths. The Idylls were published from 1859 to 1873, and included the aforementioned “Lancelot and Elaine.” Beyond Tennyson’s overflowing love for the source material, he imbues his versions of the stories with vividly precise imagery and a clear understanding of the world he wants to create in his poetry. In “The Lady of Shalott,” Tennyson tells her story alongside a narrative of the natural world, weaving in accounts of Camelot’s flora like the “Long fields of barley and of rye, / That clothe the wold and meet the sky.” As a result, this poetically visual feast is the ideal source material for Waterhouse, himself a member of the equally poetic and romanticized Pre-Raphaelite artistic movement.

Halfway between her yearning devotion and boat-begotten demise, her existence is a fragile one, heartbreaking in the inevitability of its end.

The Lady of Shalott was a young maiden of Camelot, separated from the rest of the kingdom and cursed to live alone in a tower. She spent her days singing, weaving an elaborate tapestry, and watching the world unfold without her. Over time spent gazing, the Lady fell in love with the dashing Sir Lancelot, already embroiled in a complex love affair with Queen Guinevere, King Arthur’s wife. Overcome with her passion, the Lady left her tower and descended into a boat with the intention of taking it all the way to Camelot where she would greet her lover. But she died before she could arrive and the kingdom, and Lancelot, mourned her sad end.

Waterhouse’s painting is so captivating because he manages to both freeze the narrative and encapsulate it in its entirety within a single image. Her eyes downturned and lips pouted, the Lady lies forever in a liminal space of being. Halfway between her yearning devotion and boat-begotten demise, her existence is a fragile one, heartbreaking in the inevitability of its end. The Lady’s haunting expression evokes her lovelorn nature, and the way her hair flows in the wind leads our eyes toward the stunning natural landscape around her. This evokes Tennyson’s writing, as he kept the scenery at the forefront of the poem. Waterhouse also highlights the Lady’s tapestry, made up of a series of small vignettes that further reveal the details of the narrative even for those unfamiliar with the source material. Within the tapestry, we can see a small image of a young woman in white, kneeling before a castle, as well as a knight on a white horse facing in the opposite direction. These two small pictures, woven as freeze-frames inside the larger painting, do much of the narratorial heavy lifting of the legend.

Images of women in pain pervade the literary and romantic and, when in the hands of men, perpetuate patriarchal narratives of women having to be saved.

Staring at the Lady in all her melancholy glory, I found myself thinking about the unique artistic marriage formed between poet and painter, and the way the same pieces of art take on different lives through the eyes and voices of others. From early collected myths to a large, imposing, physical canvas, the Lady has been passed through a series of hands, all in service of depicting her narrative with beauty and honesty. This ethos is at the core of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, a group founded in 1848 by a group of seven artists. Sworn to compose works depicting nature and heartfelt emotion, many of the produced paintings are of women, mostly from literature, with tragic fates. Among the founders was John Everett Millais, who, like Waterhouse, is known for his paintings of doomed women. Most notable among these is his 1852 Ophelia, which is also on display at Tate Britain. Together, these works reveal a cultural fixation, at its peak in the 19th century, with doomed women. While the Lady of Shalott herself is not a household name like Ophelia, her archetype is a staunchly recognizable one.

Standing inside the museum and unable to leave her, I felt overwhelmed by the way the Lady of Shalott and other women like her have long been controlled. Her existence becomes even more fragile when recognizing that the hands which have written and painted her have belonged to men. The archetypical doomed woman, as presented by men, is intrinsically tied to the tragic, her life never having a happy ending. While Waterhouse does not force his audiences to revel in a picture of the Lady dying, many other painters and writers do, like Millais with Ophelia, or Tennyson with the Lady. Images of women in pain pervade the literary and romantic and, when in the hands of men, perpetuate patriarchal narratives of women having to be saved. To recognize this phenomenon is not enough. It is essential to examine the historical evolutions of these tragic narratives and rewrite them. The Lady of Shalott and Ophelia prove that this is not a new concept by any stretch of the imagination. Rather, it is a longstanding one that has been able to simmer in the background of our culture and the production of media for hundreds of years, beginning with oral folklore traditions like that of the earliest forms of Arthurian legend. This is not the only narrative laid out for women in literary history. For every doomed Ophelia is someone like the sharp-minded and strong-willed Beatrice, much more active than passive. As a young woman myself, living in an unfamiliar city, I refuse to let my own narrative become one of pain and heartbreak, choosing instead to keep the Lady company and keep her fate postponed a little while longer.

Leave a comment