Evan Gold

“One night I got a telephone call from this new tenor on the scene named Wayne Shorter, telling me that Trane told him that I needed a tenor saxophonist and that Trane was recommending him. I was shocked. I started to just hang up and then I said something like, ‘If I need a saxophone player I’ll get one!’ And then I hung up. BLAM!”

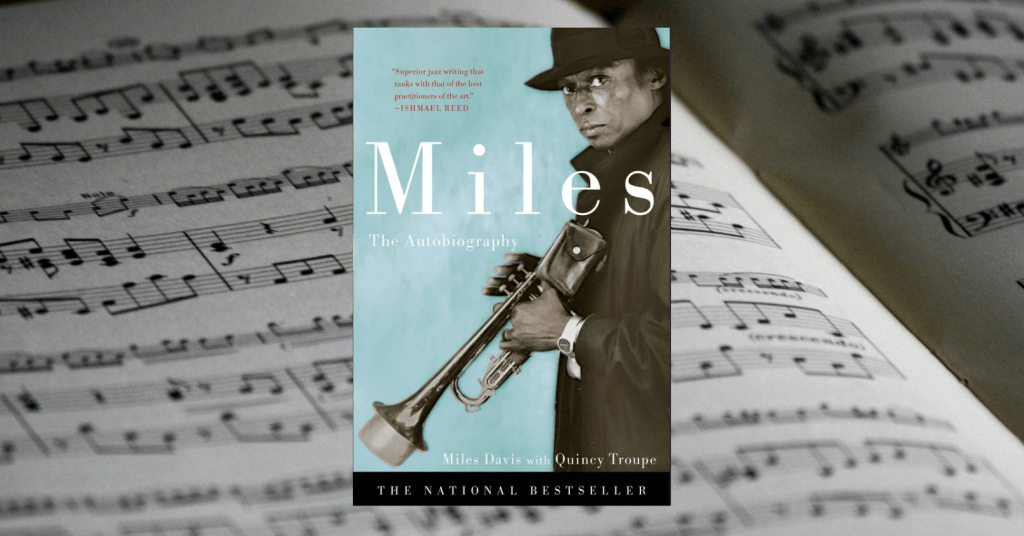

— Miles Davis, Miles: The Autobiography

First, let me preface this review by noting that I am not big on the auditory; I use my ears but think with my eyes. I read before I listen. And after finishing Miles: The Autobiography by Miles Davis and Quincy Troupe, I have read more jazz than I have ever listened to. That said, visually, Davis’s idiosyncratic voice makes this book a great read in the same way his sound makes his music a good listen, and Troupe delivers a tonal language that defines the narrative’s content. Words as applied by Davis are entirely context dependent: Everyone and everything in Miles is some form of a motherfucker. Lauded or loathed, anyone might be a clean, mean, good, or bad motherfucker. Even a description of a musician as cleaner than a broke-dick dog serves as high praise provided the right context. An attempt to read Miles is an attempt to understand the context of sound. If it helps to provide sound for context (what is a review if not more context), I wrote this review to Bitches Brew, a later album by Davis that I found quite stirring despite having the rhythmic sense of an incontinent puppy.

Few books require a soundtrack, and yet readers who are more auditory than me swear by the enlightening nature of Davis’s descriptions of his music. Take breaks from your reading to listen. Jazz aficionados recommend first relaxing your subwoofer and cleansing your palate of any abrasive ear contusions currently in vogue. It’s imperative that you find a reclined position to enjoy some certified bebop bops. Even for those with dull ears, an understanding of Davis is impossible without the impression of his music. Perhaps you can separate the art from the artist, but you cannot separate this artist from his art. So wait until an album is mentioned, then play it once your eyes tire from text.

Words as applied by Davis are entirely context dependent: Everyone and everything in Miles is some form of a motherfucker.

Percussive is the way Miles Davis the person lived to dictate the sound of Miles Davis the artist—both musically and in lifestyle—his love for music only ever rivaled by a hatred for the confines of its inception. Ever present were the constraints placed upon his sound by the labels who sought to sell what audiences already liked. Both Davises rejected the way Louis Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie would caricature themselves for white audiences. Instead, he refused to announce the titles of tracks that, he assures readers, require no introduction. Miles captures Davis as his own person. Yes—a product of his upbringing in East St. Louis, of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and John Coltrane, of New York in the ’50s and ’60s—but also as a virtuoso of self-determination. Folded into a great many pages is his grip of the music and the people he wanted to make it with.

Example:

“Trane didn’t want to make the European trip and was ready to move out before we left. One night I got a telephone call from this new tenor on the scene named Wayne Shorter, telling me that Trane told him that I needed a tenor saxophonist and that Trane was recommending him. I was shocked. I started to just hang up and then I said something like, ‘If I need a saxophone player I’ll get one!’ And then I hung up. BLAM!”

The who-do-you-think-you-are-I-am approach to his relationships both buoys his greatness and taints the nature of his gift. Left in the wake of undeniable creation are those he spurned: his sons, his wives. In the rhetoric of Davis, both greatness and greed are forms of compulsion. The people and paraphernalia are consumed by the same insatiable hunger responsible for the relentless pursuit of new sound. This motor of creative destruction is what allows him to reinvent himself time and again throughout his career.

Percussive is the way Miles Davis the person lived to dictate the sound of Miles Davis the artist—both musically and in lifestyle—his love for music only ever rivaled by a hatred for the confines of its inception.

Davis’s narrative conveys the phasic attachment of the artist to drugs, people, and musical ideas. Everything is self-referential. And maybe that punishing focus is what makes Miles so stirring as an autobiography. In reference to the death of his musical mentor, Charlie Parker, Davis laments, “I was in jail on Rikers Island when I heard about Bird’s death from Harold Lovett, who later would become my lawyer and my best friend.” That Davis doesn’t seem to care about the people in his life beyond their effect on his life adds a level of coherence to the story. His personal ideo-spirituality is entertaining and fueled by ego. There is never confusion about who he is referring to because it is only ever himself. On the following page, Davis elaborates on his predestined extradition from Rikers Island, explaining how he first interacted with Lovett like he had “been knowing him for years” and how “he’d always been able to predict shit like that.” His confounding ability as an oracle is tempered only by his unpredictable oscillation between rage and creation.

Davis’s Promethean ego defines his autobiography. As if his greatness could not be conveyed through accolades, Davis tells life like each wife, Grammy, and dollar is a reward for what he already knew he was doing right. Encompassing decades-long addictions to cocaine, heroin, and Heineken, his struggles reinforce his predestination for greatness. At best, his pride gives his narrative a brassy tone befitting his life. At worst, his prideful narrative feels like the stereo-noise ravings of an individual who so ubiquitously rejects the system that they fall into a scornful narcissistic spiral as a prerequisite for a four-year noiseless hedonistic bender. Davis never sought to give music to the people—especially the white crowds and critics—by whom much of it was received. Compared to recent captures of musical icons, he was no Flea or Bob Dylan. Not quite an optimist nor an altruist, Davis is inseparable from his sound. Miles, as narrated by Davis, is a scripture of sound—heard live or as lies. Miles: The Autobiography is a byproduct of Davis’s ego, the autobiography that his genre-defining genius demands. Like his music, the book is a story born out of a sound—linguistic context for the acoustic. It is the strength of his music that makes his narrative worth reading. My recommendation is to read in silence and listen while staring into space. I listen with spatial audio as I write. Say what you will about his music. The experience of reading Miles was, as was Davis, one motherfucker.

MILES DAVIS was a legendary jazz trumpeter and bandleader who shaped the direction of jazz in the mid-twentieth century. He died in 1991.

Miles: The Autobiography can be purchased here.

Leave a comment