Michael T. Solberg

Mornings were always disorienting. Gordon would lie there on the fringes of a dream, believing that he was somewhere else. It could be his apartment or his former girlfriend’s bed. Sometimes, it was his old room at his parents’ house. Even after he opened his eyes, there was a moment during which his consciousness lived in another place before reality wrenched it back. He laughed at himself for these daily confusions, for forgetting where he was like a child on the morning after a sleepover. But he did not dwell on the cause of these episodes, and he refused to acknowledge the yearning that underlay them.

He often received confirmation of his whereabouts in the form of Cameron whisper-shouting to ask if he was still asleep. Gordon always ignored the question, but that had never once produced the desired outcome of sending Cameron back to his own bed. Instead, Cameron would gradually move closer, the whisper-shout would become louder, and then, there would be gentle poking. Gordon hated the poking.

“Can anybody see anything?” Cameron asked after giving Gordon the first poke of the day.

“What’s he saying?” Violet asked from across the room. Her voice was hoarse and uncertain.

“He said, ‘can anybody see anything,’” Maxwell said as he sat up and stretched.

“Is that a joke?”

“No, Cameron. Nobody can see anything. It’s as dark in here for us as it is for you. Do we really have to start every day like this?” Gordon squirmed away from an incoming poke and gave Cameron a light push.

The three who were still in bed listened to the sound of Cameron tripping over his shoes and stumbling into the wall. Gordon had developed a talent for recognizing sounds. He knew by the skittering of the shoes where they had landed and how far Cameron had kicked them. He could tell where Cameron was as he braced himself against the wall.

“Oh, shoot. I think I knocked the picture off the wall.”

Then came the sound of Cameron on his hands and knees, running his palms along the floor in search of the fallen frame.

“What’s on the agenda today?” Maxwell asked Violet.

“A conversation.”

“I don’t want to have a conversation today,” Gordon said.

“It’s better than jumping jacks,” Maxwell offered.

Gordon did not engage. He also hated jumping jacks.

“What are we talking about today?” Cameron asked. He had found the picture and was scraping the metal backing against the wall, trying to find the nail that was several feet from where he thought it was.

“Today’s topics are fruit, solvable annoyances, should we open the hatch, and the meaning of life.”

Maxwell and Gordon groaned at the same time.

“Shush,” Violet said. “Both of you, just shush. When it’s your turn to lead the conversation, you can choose the topics.”

“I’m so sick of fruit,” Gordon said.

“Thank you,” Maxwell agreed. “Fruit never gets us anywhere.”

“I kind of like fruit,” Cameron said.

“Everyone, eat some breakfast and meet in the den,” Violet said. “I don’t want to hear another complaint.”

They stretched and rubbed their eyes and shuffled into the pantry, bumping lightly against each other and dispensing encouraging shoulder pats in a kind of reflexive camaraderie. Maxwell handed out the food packets and grabbed an extra one for Cameron, who was still working diligently to rehang the picture. Maxwell approached Cameron, and his hand found Cameron’s face. He patted his way from Cameron’s face to his shoulder to his arm and placed the packet in Cameron’s hand before joining the others in the kitchen.

“What did you get?” Maxwell asked.

Gordon opened his packet and coughed at the smell. “Tuna. Is it just me, or do I get tuna more often than anyone else?”

Maxwell laughed. “You do seem to get the most tuna.” He paused and opened his packet. “Don’t feel too bad. I got spinach.”

“Violet?” Maxwell asked.

“Peaches. I love peaches.”

“Cameron!” Maxwell shouted.

“Cameron here.”

“What’d you get?”

“Hang on.” Cameron opened his packet. “Chicken tikka masala.”

“That’s definitely not on the menu,” Maxwell shouted back.

“It’s chicken tikka masala,” Cameron shouted again.

Maxwell shook his head. “I’m worried about him.”

The three at the table shared their meals with each other, and when they were done, Violet collected the packets and walked them into the trash wing. She held her breath as she navigated the hall and tossed the packets into one of the pits. Then, she walked back to the kitchen and put a hand on Gordon’s and Maxwell’s shoulders. They stood and followed her into the den, collecting Cameron on the way.

When they all had sat down, Violet began. “Okay, so, thank you, everyone, for gathering for today’s conversation. Today’s first topic is fruit.” She expected objections but heard none. “We believe that we ran out of strawberries seventy-five weeks ago. Would anyone care to describe a strawberry for the collective memory?”

“I would like to describe a strawberry,” Cameron said. No one responded, so he continued. “A strawberry is like a raspberry but sweeter and less bitter. A strawberry is to a ripe peach as a raspberry is to pomegranate.”

“I’m sorry. I disagree with that analogy.” Despite his annoyance with these structured conversations, Gordon could not stop himself from participating. The others waited in silence for Gordon’s proposed alternative.

“A strawberry is to a peach. I like that because they are both sweet and juicy, but as a raspberry is to a cherry that’s not quite ripe.”

“Oh, I like that. That is better,” Cameron said. Everyone agreed.

“Okay. Thank you, everyone. Let’s all try to remember a strawberry like that.” “Mmm-hmm”s and “yep”s from the group.

“Okay, thank you. The next topic is solvable annoyances. Does anyone have a solvable annoyance they want to discuss? And, let’s just all please keep in mind how important the solvable part is.”

“I don’t think anything is annoying,” Cameron said.

“Thank you for sharing, Cameron,” Violet said.

“I would like to be able to opt out of karaoke,” Gordon said. “I can’t sing, and sometimes when I try to hit high notes, it hurts my throat.”

“Karaoke is important so that we remember the songs,” Violet said. “Is there a different annoyance that might be a little more solvable?”

Gordon paused to think. “I’d like not to have to wear a tie at the next formal gathering.”

“It’s important to remember how to tie a tie for the collective—”

“The collective memory. I know. What if I tie the tie and take it right off?”

“What does everyone think?” Violet asked. Maxwell and Cameron expressed approval.

“Okay,” Violet said. “You still have to tie the tie, but you don’t have to wear it at our next formal dinner.”

Gordon nodded to himself, pleased with the small victory.

“Maxwell, do you have any solvable annoyances you’d like to discuss?”

Maxwell thought about the question. “I could use a hug.”

“Okay. Well, so, does anyone else need a hug? We could, maybe, you know, maybe it’s a two-birds kind of situation,” Violet said.

Cameron stood up. “I could go for a hug,” he said. Maxwell stood too, and they shuffled toward each other and embraced. Cameron gave Maxwell a good squeeze and a pat on the back.

“Thanks,” Maxwell said. “I needed that.”

“Okay. Thank you, everyone, for your solvable annoyances,” Violet said when the hug was over. “I think mine would be, I’d like a little less pouting when we’re doing something that not everyone wants to do. Like, the complaining about the fruit conversation. Is it okay if we all try to be a little more positive?”

Begrudged “yeah”s followed.

“Okay, thank you. Now, let’s move on to the next topic: Should we open the hatch? All in favor?”

No one spoke.

“All opposed?”

Nays all around.

“Great. We will not open the hatch today. Now, for the last item on the agenda. Does anyone want to offer a thought on the meaning of life?”

“I think it probably has something to do with supporting your friends,” Cameron said, as he did every time the topic arose.

“Thank you, Cameron.”

“And also, the truth. Being faithful to the truth,” Cameron added.

“Yes, that is important,” Violet said.

“I think it’s about finding your place in the world,” Gordon said.

“Life transcends meaning,” Maxwell said, a new insight of which he was very proud. “But also, we should put our faith in the truth.”

“Pithy,” Violet said. “I think the meaning of life is to engage with the truth and preserve the collective memory.”

Mumbles of approval followed.

“Okay, well, thank you, everyone, for a good conversation. Enjoy the rest of the morning, and we’ll meet later for lunch.” At that, the group dispersed into the darkness.

•

Submission for the Collective Memory 622

When the lights went out, we had twenty-eight candles. In hindsight, that was not nearly enough candles to have. Rationing them seemed pointless, so we went through them in about a week. It’s funny, with all the preparation we did before we came down here, we never even considered the possibility that we could lose power.

Back then, the discussions were all about the rule of threes. You can survive three weeks without food. That seemed like a lot to me. Three days without water. Three hours without shelter in extreme conditions, and three minutes without air. Cameron used to add three seconds without friendship. I think there might be something wrong with him. Lately, I wonder if the list should have started with three years without light, but I think it’s been longer than that.

For the most part, I’ve gotten used to the darkness, but it does complicate these journal entries. I never know if my writing is crooked or if I’m starting at the right spot. Sometimes, I wonder if I’m repeating something that I’ve already written, but it’s not like I can go back and check. There’s something about our routines and the darkness that makes it hard to differentiate between what you only thought and what you actually wrote down. And as long as we’re down here, I’ll never know. I guess my point is, I apologize if I’ve said all this before.

The darkness is a challenge, but the hardest part is not knowing what happened to everyone else. I think about all the people I used to know and wonder what became of them, but we’re not supposed to do that. It just makes it harder. I also wonder about the others who found a way out and how they are faring. I hope they had better luck with their generators. As difficult as it can be down here, it’ll all be worth it when we get to meet them someday.

•

Free time was becoming problematic for Gordon. Sometimes, he would thumb wrestle with one of the others or play some game they had invented to pass the time. He had a puzzle that he could do by feeling the edges, but that was more frustrating than entertaining. Today, he just found a quiet place to sit. In these intervals of stillness, his thoughts often drifted to his parents and all the people he missed. It troubled him that some memories acquired a different tint the more he revisited them, his emotions shifting as details were added or lost. His cousin, Henry, was one of those memories, and when Gordon thought of the people in his life before, Henry was always among them.

Henry had come to live with Gordon back in high school, and it had been a difficult time for everyone. Henry’s mom was diagnosed with cancer. His dad had died in an accident a few years before, so there wasn’t anyone to take care of him. At first, Gordon thought it would be a short stay because that’s what everyone said. He and Henry had never spent much time together, so it was uncomfortable to share the same house. The worst part was that Gordon’s parents focused on Henry and showed him lenience that Gordon did not receive. When Gordon protested, they told him that he had to be nice to Henry because his mom was sick. Then, when she died, he had to be nice because of that.

And Gordon wasn’t a monster. It wasn’t as if he needed these admonishments to be kind. He would have done it anyway. When Henry’s mom died, Gordon put his arm around Henry and said he was really sorry. He gave Henry the good baseball mitt when they played catch, and he took the blame when Henry dented one of the cars with an errant throw. The kids at school used to make fun of Henry, but Gordon made sure not to join in on that. He even started to think of Henry as a friend.

He remembered one day when a group of kids were whispering about Henry in study hall. Henry was sitting at another table by himself, and he was crying a little. Not like sobbing or anything, just occasionally sniffling and wiping away the tears as they came. The other kids were making jokes and saying things about Henry that Gordon knew weren’t true, and for some reason, Gordon was overcome with anger. So, he just stood up without saying anything and went and sat at the same table as Henry. They didn’t speak. He couldn’t recall if Henry even looked at him, but he sat there until the end of the period. He used to believe that he had done the right thing, defending Henry like that, but he was no longer sure.

When Gordon told the others about Henry, Violet just smirked and said, “Beware the interloper.” It was the first time Gordon had heard that phrase, but he had heard it many times since. After talking to Violet about it, Gordon saw that Henry had taken a piece of his life. He had inserted himself where he didn’t belong and exploited the sympathy of Gordon’s parents. Looking back on it, Gordon realized that there was a lesson in that: You have to protect the things you have that are good. If only he had known it back then, he would have done things differently. That’s what he told himself, but even after all these years, no matter how often he referred to Henry as an interloper, it never sounded true, and the dissonance was making him restless.

Gordon had gotten himself worked up and decided that it would be good to move around. He made his way along the hallway, past the sleeping room, past the meditation space. He walked incautiously, knowing the way by heart. In the early days after the lights went out, their movement had been so different. He remembered how they would shuffle and stop suddenly when they felt as if there might be something in front of them. They’d shuffle-step forward. Stop. Turn their heads to the side and move their arms in all directions, repeating the process, shuffling and groping at the darkness until they ran into something. If they could have seen themselves, he was sure they would have looked deranged. But now, they knew the bunker and each other and could move with little hesitation.

At the end of the hall, there was a metal ladder with twenty-four rungs, and at the top, there was a hatch. He was only going for a walk, but when he became aware of the ladder, he stopped. Without considering it, he grabbed the rungs and began to ascend, his only intention being to get to the top. The air grew warmer as he climbed, and the sound of his feet on the metal rungs became muffled as the space narrowed. He put his hand up and felt the hatch. There was a wheel with four metal spokes. To open the hatch, he would have to turn the wheel counterclockwise and push up. The wheel was smooth and cold and did not budge with a light tug. It would require real work to open it and, just then, he felt a tectonic shift inside himself; he twisted harder and felt the wheel turn just a little. But that terrified him. He turned it back the other way, undoing whatever loosening he had caused. It might even be tighter now than it had been before he climbed up.

His heart was pounding in his ears, and his right hand hurt from gripping the ladder. He wondered what it would feel like to give in. Internally, there would be some mix of shame and liberation, exuberance, and dejection. Externally, he did not know. He assumed there would be light and that it would nearly blind him after all these years (was it really years?) in darkness. The uncertainty and shame were enough to send him back down the ladder, back through the hall and into the den where the others sat listening to Cameron playing the guitar.

“Where were you?” Violet asked.

“On a walk.”

Sometimes, Gordon wondered if Violet had evolved so that she could see in that perfect darkness. There was suspicion in her voice, as if she had watched him do what he had just done and was testing him. She made a sound in response that was neither approving nor accusatory, but he thought he heard skepticism. Or maybe the adrenaline was making him paranoid.

Gordon tried to act normal, focusing on the music and concentrating to slow his breathing. After the lights went out, Cameron set aside time to practice the guitar every day. He must have had some kind of innate musical talent because Gordon had never heard music so beautiful. Or maybe the music took on a magical quality under the circumstances, and if you plopped Cameron down in a coffee house on a Tuesday afternoon, the brilliance of it would dissipate.

“Any requests?” Cameron asked.

“Play that Beethoven one,” Gordon said.

“Für Elise,” Violet said. “You’re not even trying, Gordon. Do you even care about the collective memory?”

“Sorry. I should have been more specific.”

Cameron began to play, and everyone gave him their full attention. Gordon liked the way it sounded on a guitar. He had heard Cameron play it often enough that he began to forget what it sounded like on the piano, but he would never say that out loud.

When Cameron finished, he started to play another one without asking for a request, one that Gordon did not recognize. The atmosphere loosened when they realized that Cameron was just plucking chords, so there was nothing they needed to remember.

“How come we never even, like, debate opening the hatch?” Gordon asked.

Cameron stopped playing, and silence fell as everyone processed Gordon’s question. Then, Cameron began to laugh.

“That’s a joke, isn’t it, Gordon? Oh, you… you had me for a second,” Cameron said and resumed playing.

“Where is this coming from?” Violet asked. “Is something the matter?”

“No, I just thought… never mind. Forget I said anything. Cameron’s right. It was just a bad joke.”

“Do you need a—”

“I do not need a hug. Thank you, Maxwell.”

•

Submission for the Collective Memory 767 744

I’m not confident that our schedules are tracking with the days. I think we did all right for a while, but sometimes when I wake up, I feel like I’ve been asleep for only a few hours. And, I only bring that up because I just want to be honest about how I don’t think I can verify it. We think we’re probably sleeping at night and up doing stuff during the day, but what if our schedule slipped a little, and we’re sleeping more or less than we used to? Time is funny down here.

To be honest, I didn’t expect to be down here this long. No one ever said how long to stay away, so maybe we’re just playing it safe? We wouldn’t want to be the first to emerge. Lately, I’ve been thinking about voting “yea” when we have a conversation and ask about opening the hatch. Or maybe not “yea,” but I could try to open a real dialogue about it. I guess I could vote “nay, but” and then try to take everyone’s actual pulse on the matter. At some point, we have to go out there. The more I think about it, the more I know that we have to share the collective memory so that it’s not all lost. That’s the reason we’re doing this in the first place. It’s the whole point. But if the intent is to share it, doesn’t that mean that people in other bunkers will be sharing stuff with us, too?

I want to ask for an explanation because I really want to understand, but I think they might question my devotion. Every time I try to ask for clarification, even if it’s just a genuine question, not a challenge or anything like that, they always act like I’m renouncing everything. But that’s not it at all. I know I’m supposed to trust that what we’re doing is right, and when the time comes, it will all make sense. But the longer we’re down here, the more I wonder if I’m the only one waiting for the time to come. I’m getting a little nervous that this is it, and if that’s the case, I don’t know if I’m going to make it. I wish I were stronger like the others.

•

Karaoke seemed like a misnomer because when there was accompanying music, it came only from Cameron’s guitar. More often, the group performed the songs acapella, which resulted in varying degrees of distortion with respect to the original work, depending on their familiarity with it. After a pitchy, though faithful, rendition of “Livin’ on a Prayer,” Gordon said he needed to use the restroom and was going to grab a glass of water to soothe his throat. They reluctantly agreed to continue without him for one song. After quickly pumping himself a glass of water from the well, he walked down the hall and climbed the ladder. At the top, he turned the wheel without hesitation, hoping that the singing was loud enough so that the group could not hear what he was doing. The turning became easier, and when he stopped and pushed up, the hatch budged, dirt pouring into his face and into his eyes. He pushed harder and expected a blinding light, but there was only a dull glow. It must have been night.

He slipped a wallet through the small crack so that it might catch someone’s eye and draw their attention to the hatch. He thought about just flinging open the hatch and making a run for it, but he could not bring himself to do it. If he left now, they would disown him, brand him a liar and a traitor. The wallet presented the possibility of anonymity. If someone found them, they could emerge together, and Gordon could still be a part of it. He needed to still be a part of it.

He hated himself for sabotaging the effort and breaching the trust of the others, and if there was any other way, he wouldn’t have done it. But the more he thought about it, the clearer it became that he could not speak out. He knew how they would react, so he had to try this one last thing that might save them. And he wasn’t giving up. He didn’t think they were wrong or anything like that. He just could not abide by their methods anymore. Staying down there seemed like the right thing at first, but too much time had passed. He needed to save the collective memory so that they could share it.

He did not have time to dwell on it. There was no reversing whatever he had set in motion. He closed the hatch gently and turned the wheel until he could turn it no more before climbing quickly down the ladder. He took a sip of the water he had placed on the ground before the climb and caught his breath.

“Throat feeling better?” Cameron asked when Gordon rejoined the group. “You really went for it on that last one, Bon Jovi.”

Gordon forced a laugh. “Yeah. On that one, you have to go all out.” He sat down and listened to the discussion about what song they should sing next.

•

Submission for the collective memory 742

I’ve been thinking a lot about fruit lately. We ran out of some of it down here, but it’s probably still available topside, right? Surely, they couldn’t have destroyed all the strawberries.

All this effort to remember it for the collective memory; I think we could just wait until we go back up and eat it. Then, we’ll know what it tastes like. Or is the concern that there are false strawberries? If there aren’t false strawberries, the only reason to record their taste for the collective memory is if we don’t intend to resurface. And if that’s the plan, it’s a new one. I’d like to ask the group if they think false strawberries are a real possibility, but then I think, of course they are. Look at all the other untruths. Something as small as a strawberry would be easy enough to fake, and they’d love that, wouldn’t they? They’d love it if everyone went around believing that they were eating strawberries when they weren’t. I don’t know why I do this to myself—get all worked up when there’s nothing to be worked up about. But this is exactly the reason we need to share what we’ve preserved.

•

Gordon thought that he had dreamed the sound because he had dreamed it before, but when he opened his eyes, there was light, and he knew it was real. The sound of the hatch and the squeal of a metal hinge brought him out of his sleep.

“Holy shit. It’s one of those bunkers.” It was a man’s voice, unfamiliar.

“You’re not going down there,” another voice said. The second voice was farther away, apprehensive.

“Why not? Let’s check it out.”

“What if they’re still in there?”

The first voice laughed. “No way. They found them all. Come on. Let’s check it out.” Gordon sat up and listened to the feet on the ladder. He looked around the room and saw that Cameron and Maxwell were still asleep. Violet’s bed was empty.

Gordon stood up slowly, unsure of how to proceed. A sob ran through him. What a thing it was to see again!

“Dude, come on. Come back up. Let’s call someone.”

“Who are we gonna call? Come on, let’s check it out.”

Gordon heard another set of steps on the ladder. He wanted to call out, but something stopped him. He stood there, frozen against the wall, listening to the sound of steps negotiating the hall.

“This is wild, man,” one of the voices said.

Gordon watched the doorway to their sleeping room illuminate as the flashlight beam came closer and flitted in and out of the room.

“Okay, we’ve seen it. Can we go now?”

There was no response as the flashlight continued to advance. And then, there was a flash that blinded Gordon and the sound of a scream.

“They’re still here!” the voice shouted.

“Go, go, go!”

Gordon held his hands to his eyes and rubbed them. He blinked and saw nothing but white.

“Guys? Is everyone else seeing this?” Cameron said. “What’s happening?”

Maxwell rolled over. “Who’s there? Who’s in here? Gordon? You okay?”

“Whoa, whoa, hold on.” Violet’s voice came from the hall where the strangers were retreating. All at once, the light went out with the sound of a bang, and Gordon knew the hatch was now closed. Soft footsteps on the ladder followed, and then, there was a quiet thud as Violet hopped back down to the hallway beneath the hatch.

The light had dimmed, but there was still light coming from somewhere. Gordon’s eyes refocused, and he saw the flashlight against the wall.

“Look, we just… we stumbled on the hatch. We thought it was empty. We don’t want any trouble.”

Violet’s voice had a tone they had not heard in a long time. “Relax, guys. It’s okay. Relax. Just, come in and have a seat. Cameron?”

Cameron stood up. “Yeah?”

“How about getting our visitors some water?”

Violet said. Her voice was calm, as if she were speaking to the waitstaff at a restaurant, and they were all having a wonderful time.

“Uh, yeah, sure. Okay.” Cameron’s voice was shaky, confused. Gordon was panicked. He trembled as he listened to Cameron make his way into the kitchen and pump the water into glasses.

“Please, miss. Just let us leave.”

Gordon worried that they might attack Violet to escape. He watched the silhouettes of the men shuffle past the flashlight and wondered how she could be so composed. The shape of Violet bent down to the light, and then, the absolute darkness returned with a click.

“Gordon, Maxwell,” she said. “Why don’t you have a seat on the couch? Gentlemen, you can sit on the loveseat. Here,” she guided them to sit, and Gordon heard the weight of their bodies fall heavily on the cushions.

“We won’t tell anyone. We swear. Please. Can we please just go?”

“Well, we can talk about that. Something we like to do sometimes to start the day is have a conversation. You can join us today. Cameron?”

“Here,” Cameron said. He held out the water until the glasses pressed against the chests of the strangers, both of whom jumped at the touch, and some of the water spilled. “Oh, sorry. Sorry. You get used to the darkness,” Cameron said. “Here. Easy does it.” The strangers took the water, but there was no sound of drinking.

“Well, this is actually a nice surprise,” Violet said. “We have an opportunity for a new topic.”

“We’re still doing fruit though, right?”

“The new topic,” Violet said, ignoring Cameron, “Is what brings you here? Let’s start with our new friends.”

No one spoke through the sound of heavy breathing.

“Oh, don’t be shy. Please. Tell us what brings you here today.”

“We… we were just hiking, and we saw a wallet on the ground, and when we picked it up, we saw the hatch. We thought we would take a look because—”

“A wallet? By the hatch?” Violet interrupted.

No one spoke.

“Whose wallet?” Violet asked.

“I don’t know. Just a wallet. Some guy named Steve, I think. Steve K-something.”

“Kastenbauer?” Violet asked.

“Uh, yeah. Sure. That sounds right.”

“Interesting. We’ll talk about that in a minute. What happened after you saw the hatch?”

“We thought it might be a bunker,” the stranger continued. “And they said that they thought all the bunkers had been found. Your movement—everyone else is out. Most bunkers weren’t built to last that long. That guy who started it was cr… he was unwell. He lasted like four days before he bailed. We just wanted to see what it looked like, and we thought it would be empty.”

“That isn’t true,” Violet said.

“What?”

“What you said. It isn’t true. The movement hasn’t ended. You’re lying. Did they send you down here to try to trick us into leaving?” Violet laughed. “Pathetic.” She laughed again. “That’s pathetic.”

“It’s true. There were news stories. You guys think you’re down here preserving the truth or whatever, but you’re the ones who were lied to. Here. I’ll show you.” One of the strangers pulled out his phone.

“Put that down!” Violet shouted. “That’s your truth. Not ours. They found all the bunkers? You’re standing in one. How can you tell me they found them all? You’re telling me the place you’re standing in doesn’t exist. Don’t you see? Don’t you see that you can’t trust them?”

Gordon assumed that the strangers were trying to look at each other, trying to decide what to do. He felt a pulse of nerves and started to become nauseated.

“Where are your parents?” The one who hadn’t spoken asked.

Violet scoffed. “Our parents? How old do you think we are?”

“Sorry. I’m sorry. It’s just, this bunker is huge, and in the light, you looked so young. Someone with a lot of money must have—”

Gordon heard the sound of one stranger elbowing the other, the sloshing of water.

“The bunker belonged to Steve. We met him online, and he said he had a bunker that would fit us all. When the generators went out, he wasn’t as committed as we were. It was sad to lose him like that, all the dignity gone out.”

“Oh, God,” one of them said. “Please. Please don’t kill us.”

“Kill you?” Violet laughed. “We’re not murderers. We’re here to preserve the truth. Do you know how many lies they feed you every day up there? Steve is in his room. He was threatening to open the hatch, so we had to put him somewhere where he wouldn’t jeopardize the movement.”

One of the strangers made a sound that was something like a whimper. The other one spoke. “Look, we’re just going to go. We won’t say anything to anyone, and you can stay down here as long as you like.”

“Well now that we have your permission, we might just do that.”

The men stood up and stumbled over the furniture. There was the unmistakable sound of someone racking the slide of a handgun. Gordon had heard it in movies all his life, but down there, it sounded like the loudest sound in the world.

“Violet?” Maxwell asked.

“Shh. It’s all going to be okay.”

“What’s happening?” Cameron asked.

“I thought you said you threw that in the trash pit after Steve—”

“I thought we might need it, and now we do, so everyone, just shush. You two, I’m sorry, but you’re going to have to go into Steve’s room for now until we decide what to do. It’s the only one with a lock.”

“Oh, Violet,” Gordon said.

“I said shush! You of all people should know when to keep quiet.”

There was the sound of Violet herding the strangers to Steve’s room. They heard her undo the makeshift latch that they had installed after Steve tried to leave, and then, the door shut, and Violet relatched it.

Then, there was pounding and screaming.

“Violet,” Gordon said. “Steve… he stopped eating the food we brought him ages ago. He must be—”

“Careful,” she said. “Careful what you add to the collective memory. Steve was okay the last time we saw him, and so were those guys.”

There was a pause filled with heavy breathing.

“Gordon, any idea how Steve’s wallet got out there?”

“What are you talking about?” Cameron asked.

“I knew I heard you on the ladder,” Violet said. “I knew it. Gordon doesn’t want to be part of the movement anymore.”

“No, that’s not—”

“He put Steve’s wallet up there so that someone would find us out. He’s a coward. Worse. He’s a liar.”

“Gordon?” Maxwell asked. “Steve must have dropped his wallet on the way down, right?”

Gordon did not respond. He was thinking about the days leading up to their first day in the bunker and how excited he had been. It was such a beautiful sacrifice to make.

“I think they deserve the truth,” Violet said.

“I’m sorry,” he whispered.

“All in favor of having Gordon join the interlopers in Steve’s room?”

No one spoke.

“All opposed then?”

Silence but for the screams coming from the room where the hikers were locked.

Gordon thought about his journal and the good that it might do. It was his most important possession, and he was proud of it. But now, he worried that the others would find it and destroy it, and then, it would be as if he had never come down here at all. Or worse, they would find it and read it, and it would contain nothing that had not already been preserved or nothing worth preserving. He closed his eyes and wished for it to be a dream, but the screaming did not stop as his mind grasped for something to hold onto in the darkness, stutter-stepping and flailing along the nascent edges of doubt.

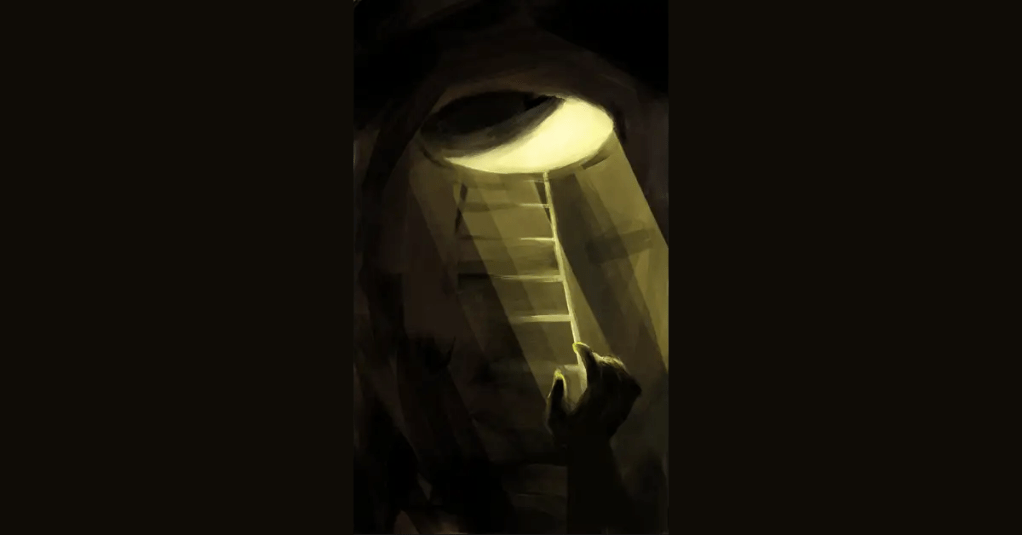

“The Hatch” by Michael T. Solberg and the artwork titled You Get Used to the Dark by Roger Ratanapratum appeared in Issue 44 of Berkeley Fiction Review.

Michael T. Solberg is is a writer and attorney located in Madison, Wisconsin. This is his first published story.

Roger Ratanapratum is a senior landscape architecture student, and he specializes in character art and illustration in his free time. He has previously submitted one other illustration for the Berkeley Fiction Review back in his freshman year, and he was delighted to round off his four years of college by painting another. He has also contributed to Let’s Rock! – A GG25 Fanzine, a free community publication celebrating the Guilty Gear series’ 25th anniversary.

Leave a comment