When we think of famous literary mothers, the nurturing and uncomplicated ones tend to place foremost in our minds. Marmee, from Little Women, with her sensible advice and poise. Mrs. Weasley, known for her ceaseless kindness and fierce, protective nature. These motherly figures often serve as support or motivation for the protagonist: loving figures that encourage them to endure in the face of hardship. Perhaps our thoughts even drift towards the notoriously villainous: Carrie’s infamous Margaret White, or Coraline’s duplicitous, monstrous Other Mother. They are obstacles to overcome, the paramount representation of the character’s struggles, and their defeat is a sign of growth over the course of the story.

However, motherhood can be much more complicated, blending the good with the bad, and ultimately deeply affecting a child in a subtler way.

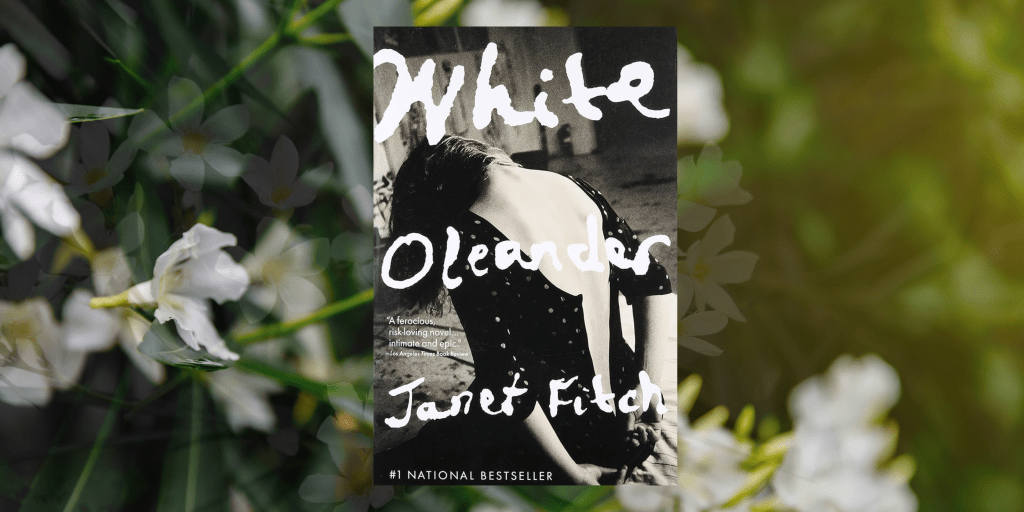

While these two archetypes may fall on opposite ends of the moral spectrum, they are united in their simplicity. They are either good or evil, a hindrance or a help, clear-cut as one or the other. In a sense, their binary nature contributes to their iconic status; it’s very easy to recognize and emotionally react to someone portrayed as purely good or purely evil. However, motherhood can be much more complicated, blending the good with the bad, and ultimately deeply affecting a child in a subtler way. In Janet Finch’s White Oleander, readers explore the beauty and toxicity of a flawed mother-daughter relationship through a narrative that teaches us nothing is as it seems.

White Oleander follows Astrid, a young girl orphaned and thrust into the foster care system after her artist mother is imprisoned for poisoning her boyfriend. Throughout her journey, Astrid encounters several foster mothers who represent different lessons about life and womanhood. While many of these women are interesting, multifaceted characters, the story highlights two as its main focus: Astrid’s biological mother, Ingrid, and her favorite foster mother, Claire. Each woman is incredibly flawed, albeit one more than the other, yet they demonstrate moments of tenderness, imparting lessons and giving Astrid gifts and advice that prepare her for adulthood. In this way, each woman simultaneously fulfills some of the “good” motherly expectations while also harming Astrid with their worst traits, complicating their role in the narrative.

Ingrid, Astrid’s biological mother, is a free-living artist and poet who refuses to be tied down by the material world. She’s deeply narcissistic, jealous, cruel, and manipulative; obsessed with physical beauty, she mocks or demeans those she perceives as beneath her. Ingrid neglects Astrid heavily, ignoring her educational and nutritional needs, and in an extremely selfish and disturbed moment, kills her boyfriend with no regard for how this action will affect her daughter. This causes Astrid to enter the foster care system, where she is abused in multiple households. And yet, her mother expresses no regret for Astrid’s suffering as a result of her choices. She is even implied to have contributed to the suicide of Astrid’s favorite foster mother, Claire, through manipulative letters that destroy Claire’s psyche, out of jealousy that another mother would reign supreme in Astrid’s heart.

With these events in mind, Ingrid seems poised to be the “evil” mother, a cartoonishly villainous figure who exists as Astrid’s main antagonist, waiting to be triumphantly conquered. However, she and Astrid have a far more complex relationship. Despite her cruelty and desire for total control, Ingrid displays real affection for her daughter, asking her to write and draw about her experiences and giving her advice that allows Astrid to survive her hardships. At the climax of the story, she decides not to ask Astrid to lie for her at the trial, allowing her daughter to heal rather than prioritizing herself. At the end of the story, Astrid still loves and longs for her mother, as toxic as she is.

Meanwhile, Claire appears to be Ingrid’s exact opposite. She’s kind, sensitive, caring, and gentle: the seemingly perfect mother who Astrid becomes deeply devoted to. She waits for Astrid to get home after school each day, makes her food and buys her gifts, all while also making an effort to listen to and understand Astrid’s life. However, her love is damaging, just as Ingrid’s is. She heavily relies on Astrid as an emotional confidant and often tells her things a child shouldn’t have to know. She becomes dependent on Astrid, using her to fulfill a need for connection and purpose rather than loving Astrid as she is. As she becomes increasingly depressed, she too begins to neglect Astrid and eventually commits suicide, leaving Astrid again without a mother and deeply traumatized.

Good and bad are intertwined, and Astrid chooses what parts of these mothers she brings with her into the present.

Both Claire and Ingrid show affection to Astrid; they give gifts, bake cookies, and compliment her just as the typical “good” mother would. Astrid genuinely loves both of these women at the end of the novel, and as the reader, we can see why she loves them. But we also understand that their love is ultimately self-serving and incredibly abusive. Ingrid is a poster child for narcissistic abuse and neglectful parenting, while Claire forms a codependent, emotionally abusive relationship that was designed to benefit herself, not Astrid. But they aren’t Astrid’s final obstacle that she gleefully slays to “complete” her character arc. Instead, Ingrid chooses to let Astrid go instead of selfishly making her testify, and after Claire’s death, Astrid brushes her hair and arranges her as if she were sleeping. Neither relationship fits cleanly in the boxes of “good mother” or “bad mother”. Instead, much like relationships in the real world, it’s complicated. Good and bad are intertwined, and Astrid chooses what parts of these mothers she brings with her into the present.

After aging out of the foster care system, Astrid becomes an artist who literally transforms her emotional baggage into physical baggage: creating mini dioramas of her mothers in vintage suitcases she carries around. Claire and Ingrid both feature prominently, with these boxes described as being particularly beautiful and ornate. Astrid reflects on her mothers, listing the ways in which they contributed to the person she is today.

“Like guests at a fairy-tale christening, they had bestowed their gifts on me. They were mine now.”

And this is the intoxicating beauty of White Oleander’s take on motherhood: it’s impossible to simply categorize. Love and beauty, abuse and pain, and mother and daughter, come together in so many different forms. The bonds shared by a mother and child can be what drags a person back, ensnaring them and silencing their cries, and yet, it can be what binds them together into someone new.

Leave a comment