1. Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation

When the German asks me questions, it can feel like an interrogation. I’m not sure if this is because popular American media has entrenched within my brain the association of German accents with authoritarianism or if this is a result of discomfort regarding my lack of control. He sometimes quizzes me, unprompted, about general knowledge of European history [I get defensive, very American]. It is sometimes about my past, my time living in Paris [rainy] or Beijing [smoggy] or Maryland [stop prying].

There is one question I am unable to answer.

I not only have an inability to describe my own writing, both process and product, but I am completely at a loss whenever someone asks me why I write. It is not just the weight of it, the fact that my every breath is contingent on its literary merit, that I construct and reconstruct my reality to align the motifs, that I can not sleep without it all making thematic sense. Nor is it the pressure to vindicate, to defend my dedication to a hobby which will bring me neither money nor prestige. [Although it may be entertaining to find me at a social function, where one can observe my extemporaneous justifications for the pursuit of writing become increasingly elaborate and convoluted with each glass of wine I consume. I never give the same answer twice. It is both a comical and pitiful sight to watch someone try to convince themselves of what they’re saying in real time.]

My real trouble is that I just don’t think writing is a format suitable to be described through standard verbal [albeit mildly slurred] communication. Any attempt at doing so, by me, at least, results in a series of unintelligible stammerings and heat-flushed cheeks.

Let me try this again.

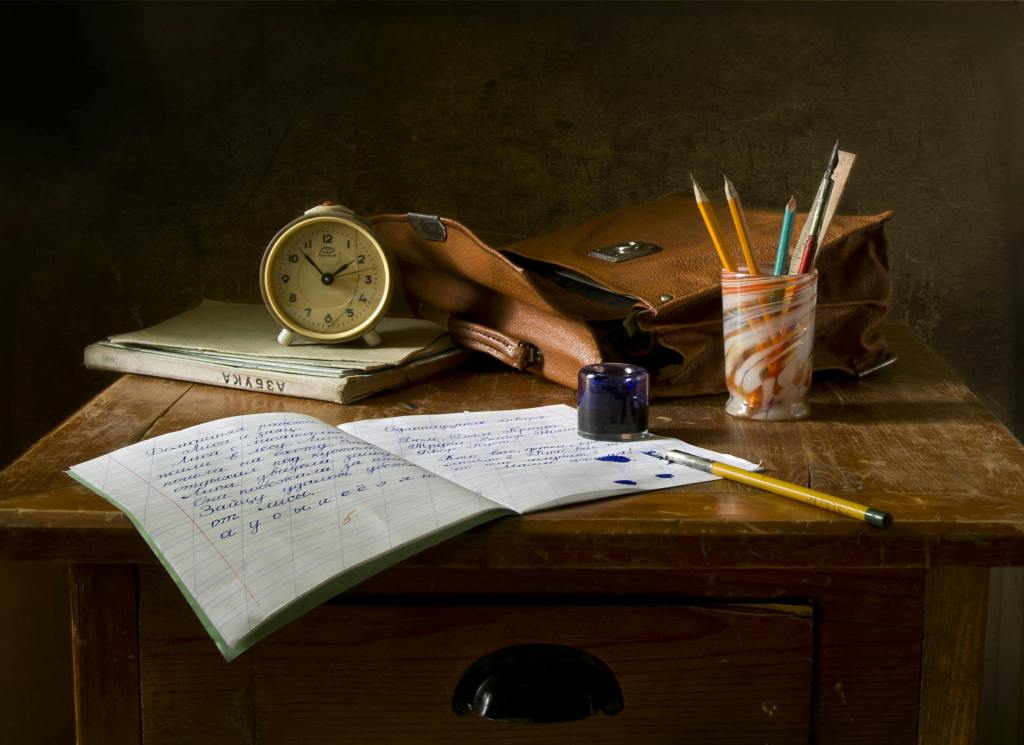

I would preface this by informing you that I was not particularly cool in grade school, but you may have already gathered that. Oftentimes, people who, for whatever reason, feel as though they don’t “fit in,” or have felt “left out” for significant portions of their life, experience intense psychic pain and/or loneliness as a result. The fundamental source of this pain is usually not that these people have been ostracized from society in a literal sense—on the contrary, they are likely the keepers of their own misery through self-isolation. I believe this pain stems from the mismatch between internal self-conception and external perception, and the utter inability to maintain control over this disparity.

In other words, I don’t feel like a loser, but why do people treat me like I am?

Well, because the tangible world is cruel and limiting. The reality is that we, by nature of interacting with other conscious beings, relinquish some control over a part of ourselves, the part which is observable by others. Try as we may, we as a species are actually not very good at manipulating our own public perception. In fact, earnest attempts at doing so will conversely spotlight these inconsistencies between our internal and external selves, leading only to further humiliation. Think of the example of a socially awkward high schooler on a Monday morning in homeroom, bragging conspicuously about his clearly exaggerated, if not outright fabricated, wild nights of delinquency and hedonism from the previous weekend. Not only does this expose his desperation for the approval of his peers, and a clear dissatisfaction with the positioning of his external self, but also demonstrates a complete failure in trying to control the way his fellow students perceive him.

I think the inexplicable drive which propels writers towards their [our] craft is substantially borne out of our inability to adequately reconcile our observed representations with our unobserved selves

I would like to break down these incongruent selves into two camps: the observable (what others perceive), and the unobservable (what goes on inside your head). Arthur Schopenhauer describes this conflict in one of his many volumes of The World as Will and Representation. He expresses the conflict that arises from the realization that our physical selves are given in two different ways: “It is given as Representation (i.e., objectively; externally) and as Will (i.e., subjectively; internally)” (Shapshay, 2018). Our inability to merge our Representation and Will [observable and unobservable selves] is, as Schopenhauer claims, the root of all human suffering from which we have no conceivable escape [Germans…]. He does, however, provide the caveat that aesthetic contemplation can momentarily provide relief from this otherwise unrelenting cycle of unfilled desire. He compares artistic experience to the sublime [das Erhabene]: the process of surrendering one’s desire for control over their incongruent selves in order to become a “pure, will-less subject” (Schopenhauer, long time ago).

I think the inexplicable drive which propels writers towards their [our] craft is substantially borne out of our inability to adequately reconcile our observed representations with our unobserved selves. Writing lends value to the intangible, which can be particularly attractive to those who are acutely dissatisfied with the tangible. I myself am not able to accept that all that exists in a meaningful way is tangible, because I would like to believe that there is so much more to my self than the few bumbling phrases I cobble together each day. I so often avert my gaze, conceal uncertainty behind false platitudes, tremble when there is no reason to.

Because how can I possibly look someone in the eyes and say something like this: I’m wondering if my urge to write is the same as my urge to be loved. To reveal the unobserved parts of myself, to somehow make them observable, and to have someone care enough to observe them.

2. Skin, or aesthetic contemplation

Schopenhauer claims that aesthetic contemplation can temporarily merge Appearance and Will, or at least obscure the boundary. He describes this as the fusion of subjective sensation, which is “limited to [the] skin,” and of objective perception which exists outside the skin, where one no longer perceives the external as something inherently separate from themselves. An experience of becoming unbound from one’s own skin, if only for a moment.

In the unedited version of David Foster Wallace’s 2003 interview with German broadcasting station ZDF [Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen], which my psychoanalyst would say I have watched a normal amount of times, he also mentions the transcendent power of aesthetic contemplation in relation to skin. He describes literature as a form of magic which allows us to “[know] what it’s like to be inside somebody else’s skin.” Wallace discusses the comfort derived from the immersive quality of inhabiting the skin of the novel, the relief from reading the innermost thoughts of another person and thinking so I’m not alone. And, always the contrarian, he also identifies a piercing discomfort within this immersion: being forced to confront the difficult and often unresolved [within himself] aspects of the human condition with visceral closeness.

I have realized that I needed to become a writer precisely because of these intense, and not always pleasant, skin-to-skin interactions with literature that I’ve experienced all my life. By that, I mean reading. Urgently, feverishly, constantly.

While my urge to write has remained constant over my years as a writer—this urge which I’ve now identified as efforts to translate my unobserved self into something observable—my actual writing, in both style and [occasional] substance, has evolved drastically. And the way I did this, the way I have learned and continue to learn how to write, sounds so idiotically simplistic that I almost don’t want to admit it.

3. Brute force method: writing on writing

Over the past few weeks, I’ve been more or less pretending to study for the verbal reasoning section of the Graduate Record Examinations. As in: glancing over preparation materials, pushing them around on my plate, contemplating, at length, the plethora of shortcomings regarding standardized testing and what it is intended to measure. Trying, by brute force, to memorize hundreds of outdated and unnecessarily obscure vocabulary words, and then calling up my lexiconally-gifted friends to complain.

It goes a little something like this:

M: Hi beautiful.

LGF: Stop calling me and do your work.

M: I think I need to hire a dominatrix just to stand over me and force me to study.

LGF: That’s not a bad idea.

M: Preferably German.

LGF: I’m hanging up now.

M: Wait wait wait. This is relevant to the GRE. Okay tell me if you’ve ever in your entire life heard of the following words. Munificent. Parochial. [I have trouble pronouncing this one] Laconic. Acrimo—

LGF: I think laconic has something to do with speech.

M: Aberration. Castigate. Parsimonious.

LGF: I get it. It’s ridiculously hard.

M: All these years of reading David Foster Wallace have literally amounted to nothing.

LGF: Well, not nothing.

M: Then what.

LGF: Celibacy?

I’m wrong, obviously. About both my ineffective studying methods and the inefficacy of reading. The way I “learned” how to write is literally just by reading and then copying. That’s it. [OK, here I should also lend credit to my writing teachers who have all been literal angels from heaven vis à vis their unwavering encouragement and guidance. But what I’m specifically describing here is the experience of sitting alone in your bedroom, man vs. blank page, face reflected ghoulishly in the dark window pane above your desk, and conquering the white space].

Some artists may describe this as their flow or being in the zone. I consider it to be a form of absolute submission to the subconscious.

It’s kind of like one of those Facebook multi-level-marketing schemes: my sublime experiences with reading drove me to become a writer, and in order to function as a writer, I must continue to read. I copy everything I read—style, structure, diction, themes, syntaxical rhythm. My writing reeks of the voices of my literary influences. In relation to academia [I can’t help but associate the word copy with plagiarism], or even artistic copyright infringement, this admission feels deeply unkosher. All I can offer in defense is to ask that you trust me that, whilst initially attempting to emulate someone else through writing, there comes a point when I am no longer in full control of what goes on the page, and something else entirely takes over. Some artists may describe this as their flow or being in the zone. I consider it to be a form of absolute submission to the subconscious.

This is why I’ve always been suspicious of the brute force method of “learning” how to write through books that claim to provide instructions on doing so. I have, of course, also been influenced by the commonly held view among other writers, many of whom could afford to receive a college education, that these books are crap. To some extent, I have to agree—reading directly about other people’s writing process is like hearing about people’s dreams. It’s mind-numbingly dull, despite the viscerality of their private lived experience. This is simply not the way unobserved experience can be translated into an observable form. One of the primary shortcomings of writing on writing is that, in order to effectively communicate intangible ideas, they must actually be obscured by the tangible form in which they are communicated.

4. Shklovsky’s “Art as Technique”

Viktor Shklovsky’s essay “Art as Technique” is often cited as the first piece of work to coin the term ostranenie [остранение], roughly translating to defamiliarization in English. Shklovsky mainly discusses the usage of ostranenie in Tolstoy’s work for political and social imperatives—to reawaken the public to e.g., the horrors of war and poverty by crafting strange and unfamiliar ways to describe them. He gives the example of Tolstoy’s omission of the word “flogging” in his piece “Shame[!],” forgoing absolute clarity in exchange for involuted imagery by describing the process as “rapping” on and “lashing about on the naked buttocks.” Tolstoy uses his own form [written language] to partially obscure the inactive word “flogging,” in order to defamiliarize the concept itself and make it strikingly sensory.

I actually think Schopenhauer, though he lived and wrote an entire century before Shklovsky, was able to vividly describe the concept and artistic intentions of ostranenie. He instead uses the term “will-less” [willenlos]. Here’s The World as Will and Representation again, paraphrased for her pleasure:

“Aesthetic experience consists in the subject’s achieving will-less perception of the world. In order for the subject to attain such perception, her intellect must cease viewing things in the ordinary way. […] In other words, will-less perception is perception of objects simply for the understanding of what they are essentially, in and for themselves, and without regard to the actual or possible relationships those phenomenal objects have to the striving self.” (Shapshay, 2018).

I feel that this description perfectly encapsulates the “make it strange” mantra of using ostranenic craft to overcome the boundary which separates complacent from critical thinking. It is not that the world itself is inherently mundane or unworthy of analysis—it only appears this way when presented through commonplace language and situation. This is often how writing advice appears to me: contextualized, familiar, beginning and ending as simply words on a page. My body and soul impermeable, not the least bit bewitched.

In his 2003 ZDF interview, David Foster Wallace remarked that the real and hard things we need to think about cannot be done in the way we conduct normal public communication. He proves his point in the same interview while, profusely sweating, attempting to critique consumerism and advertising and, before going off on a tangent about the type of cars we drive in America and maybe one of the oil crises, their role in the creation of a morally-impoverished generation that has something to do with developing hopeless addictions to the somewhat metaphysical concepts of worship/giving yourself away/addiction itself. He pleads, in what may actually be genuine earnest, to trade jobs with the cameraman.

I have a strong sense that discussion of such real and hard things must be done through strangeness and defamiliarization, through obscuring truth and creating contradictions, in order to really feel it in our bones, in order to overcome the boundary between your skin and my skin and transmit this information in meaningful ways, particularly in areas where objective public discourse has failed us. Put simply: it must be done through craft. In other words, a book worth reading transforms these complex ideas and feelings and observations into literature because they simply could not be understood any other way. The process of this transformation [writing], which is itself private and inherently unobservable, must also be subject to similar constraints. Attempting to approximate the unobserved act through detailed explanation and objective analysis, or as Schopenhauer would put it, to attempt to capture intuitive knowledge propositionally, will only lead us further astray from the initial meaning.

In other words, a book worth reading transforms these complex ideas and feelings and observations into literature because they simply could not be understood any other way

Craft itself cannot be adequately described, explained, and taught through the ordinary, straight-forward communication styles in which we conduct the rest of our public lives. If it could, craft itself would not exist. It exists to capture the ephemeral, intangible, private, and the unobserved. It exists for the sensitive. It exists for the ego. Sometimes while writing, I catch myself at the keyboard in a flicker of lucidity and sometimes my hands are not trembling. This means something. I cannot tell you what.

The World as Will and Representation (1818). Arthur Schopenhauer.

“Schopenhauer’s Aesthetics” (2018). Sandra Shapshay. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/schopenhauer-aesthetics/

“David Foster Wallace unedited interview (2003).” Manufacturing Intellect. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iGLzWdT7vGc&ab_channel=ManufacturingIntellect

“Shame!” (1895). Leo Tolstoy.

Leave a comment