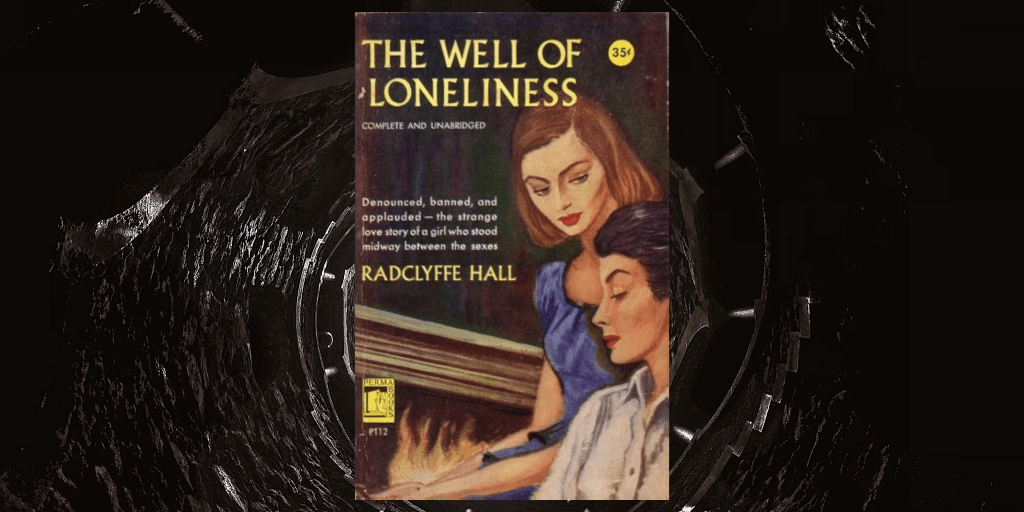

The Well of Loneliness (1928) by British author Radclyffe Hall is controversial in every conceivable way. Though it’s regarded as the first lesbian novel ever published in English, it’s by no means considered a classic today—with moral critics in 1928 condemning it as obscene and modern critics calling it “the worst book yet written.” Even within the confines of queer literary circles, the novel has largely faded from memory. So what happened?

The Well of Loneliness follows the life and upbringing of Stephen Gordon, an Englishwoman born to wealthy parents whose queerness is apparent from an early age. Throughout the novel, she struggles to understand her own gender and sexuality, and despite her many relationships with women, she continues to be haunted by feelings of social isolation—largely fueled by the rejection she felt from her own mother.

At the time of its publication, conservative courts ruled that the novel’s portrayal of “unnatural practices between women” demanded a total ban of sales in England. Yet by then, the “damage” had already been done. The legal battles faced by The Well of Loneliness drew attention to the novel, launching it into popularity across Europe and America. Not only did copies continue to circulate, but the book was branded as “the bible of lesbianism” for often being the first source on queerness that young people could find.

Fast forward to today, and opinions have changed dramatically, with academia now being the ones to target the novel with sharp criticism. Some scholars express a downright disdain for the novel, citing its poor prose, dated politics, and a storyline that makes for a miserable reading experience. Others compare it unfavorably to critically acclaimed classics of the time that also explore gender and sexuality, with Orlando by Virginia Woolf being a common point of comparison.

The dust created by endless debate has buried the narrative so deep underground that only the most dedicated readers would bother to unearth its grave.

The prevailing verdict in 2024? The novel is embarrassingly mediocre. Regardless, the dust created by endless debate has buried the narrative so deep underground that only the most dedicated readers would bother to unearth its grave.

While I’m far from a literary expert and don’t disagree with the aforementioned criticism, today I intend to dig deeper. Even after 95 years of discourse, the novel still has something crucial to offer to the modern queer kid—a raw reflection of adolescent queer experience that’s terrifyingly recognizable even today.

The Well offers brutal, authentic portrayals of complex queer identities and the societal weight they carry, delivering its message with an emotional intensity that demands to be remembered.

Gender and Sexuality: Allies, not Adversaries

Stephen Gordon’s relationship with gender and sexuality is complicated. While The Well is often labeled as a “lesbian novel” and has been celebrated as such throughout history, Stephen also embodies elements of transness as it is understood today. She rejects feminine norms of the time period, forming a bond with her father that more closely resembles a father-son relationship—something Stephen often wishes it was. Hall writes:

“In these days Stephen clung more closely to her father… they would walk hand in hand with a deep sense of friendship, with a deep sense of mutual understanding. She must tell him her problems in small, stumbling phrases. Tell him how much she longed to be different.”

Many scholars suggest that, given contemporary understandings of gender and sexuality, the novel may be more accurately read through a trans lens rather than a lesbian or sapphic one. However, it is precisely this dynamic between gender and sexuality that makes Stephen’s character a raw representation of queer identity, describing how LGBTQ+ people may embody both.

Although the novel stumbles through attempts to describe queerness politically, only capable of offering up early understandings of the labels, the authentic description of Stephen’s experiences—being attracted to women but presenting masculine—paint a messy, but genuine picture of queerness.

Stephen can be read as a representation of both of these labels, but the fact that she simply exists as an “invert”—as Hall describes it—allows for a more complex understanding of LGBTQ+ identities as they exist in reality and outside of textbook definitions. Although the novel stumbles through attempts to describe queerness politically, only capable of offering up early understandings of the labels, the authentic description of Stephen’s experiences—being attracted to women but presenting masculine—paint a messy, but genuine picture of queerness.

Instead of separating gender identity and sexual orientation, Stephen exists as a “queer person” in a more holistic sense, creating a character with experiences that offer a candid portrayal of queerness, and one that may resonate with many readers even today, despite the wider range of vocabulary we now have to describe these identities.

Queer Adolescence: A Childhood Spent in Secrecy

Additionally, The Well vividly portrays the harsh and brutal realities queer individuals face as they navigate adolescence in a society that rejects their existence. Stephen herself often encounters resistance when pursuing the hobbies she loves which are far from “ladylike.”

To achieve this portrayal, the novel captures uncomfortable, confusing, and humiliating experiences of queer childhood—in which self-discovery is made more difficult by the moral judgment of others and society at large. Stephen alone must grapple with her attractions and sense of self, often without the language to understand or explain her feelings.

Just as Stephen is coming to understand herself, she experiences an inexplicable attraction to her maid and an intense jealousy toward the woman’s male partner. This stage of self-discovery is messy yet beautifully candid, as Stephen feels both confused and frightened by emotions she cannot name but instinctively knows are dangerous.

Following this idea of the implications of holding a queer identity within society, the novel also explores Stephen’s complex and painful relationship with her mother. Hall chillingly portrays the raw internal conflict her mother faces in accepting Stephen’s identity, as though Stephen’s very existence is an offense. Her mother see’s Stephen’s masculinity as a distorted reflection of her father, as Hall illustrates:

“This likeness to her husband would strike her as an outrage—as though the poor, innocent seven-year-old Stephen were in some way a caricature of Sir Philip; a blemished, unworthy, maimed reproduction.”

This resentment manifests in extremes, with her casually remarking that:

“She hated the way Stephen moved or stood still, hated a certain largeness about her, a certain crude lack of grace in her movements… and at this thought her eyes must fill again, for she came of a race of devoted mothers.”

While some critics have pointed to this aspect of the novel as melodramatic—or even harmful to the queer community for its “promotion” of queer misery—many readers may find catharsis in its brutal but real depiction of the queer experience. For those who relate to the narrative, The Well provides a sense of visibility and voice to feelings that are often silenced or dismissed in everyday life.

Well of Loneliness: Trash or Treasure?

Hall’s motivation for writing the novel is clear from the start: to ensure that LGBTQ+ people are seen and heard. The Well of Loneliness offers a raw and authentic portrayal of the complexities of queer identity, as well as the crushing societal weight they carry. Radclyffe Hall tells this story in a blunt and unflinching manner, a narrative that can strike at the hearts of those harboring prejudice while also resonating deeply with those who share similar stories.

In many ways, she succeeded in her time. During the aforementioned trial over the book’s publication, thousands wrote to her in letters of support, with one enduring testimony from a 19-year-old lesbian standing out: “It has made me want to live and go on.”

Even as far back as 1928, the novel has managed to capture the confusion, isolation, and discomfort of growing up queer.

The Well may not be considered a literary masterpiece: the prose is messy, its identity politics are outdated, and it has struggled severely to stand against the test of time. However, even as far back as 1928, the novel has managed to capture the confusion, isolation, and discomfort of growing up queer.

In doing so, it has provided a sense of visibility and validation for countless individuals who, like Stephen, felt they had no name for the feelings they harbored. The novel’s widespread circulation has allowed these stories to reach many who might otherwise have felt alone. For that reason, The Well of Loneliness deserves to be remembered and, more importantly, read—especially by queer youth who may still struggle with feeling unseen in today’s world.

RADCLYFF HALL (1880-1943) was an English poet and novelist. Born to a wealthy English father and an American mother in Bournemouth, Hampshire, Hall was left a sizeable fortune following her parents’ separation in 1882. Raised in a troubled environment, Hall struggled to gain financial independence from her mother and stepfather. As she took control of her inheritance, Hall began dressing in men’s clothing and identifying herself as a “congenital invert.” In 1907, she began a relationship with amateur singer Mabel Batten, who encouraged Hall to pursue a career in literature. By 1917, she had fallen in love with sculptor Una Troubridge, a cousin of Batten’s. After several poetry collections, Hall’s second novel The Unlit Lamp (1924) was published, becoming a bestseller shortly thereafter. Adam’s Breed (1926), a novel about an Italian waiter who abandons modern life, earned Hall the Prix Femina and the James Tait Black Prize, two of the most prestigious awards in world literature. In 1928, Hall’s sixth novel, The Well of Loneliness, was published to widespread controversy for its depiction of lesbian romance. While an obscenity trial in the United Kingdom led to an order that all copies of the novel be destroyed, a lengthy trial in the United States eventually allowed the book’s publication. Recognized as a pioneering figure in lesbian literature, Hall lived in London with Una Troubridge until her death at the age of 63.

The Well of Loneliness can be purchased here.

Leave a comment