Note: This article contains minor to moderate spoilers for the following books/films: The Final Girl Support Group by Grady Hendrix, Final Girls by Riley Sager, X (2022), and Scream (1996).

Axes swung, fight-or-flight responses discharged, blankets donned in the back of an ambulance. A slasher film that features a final girl is nothing short of formulaic, but that doesn’t stop us from watching. I’ve always viewed the final girl trope as empowering, an opportunity for an unlikely female character to defy the odds and be the last one standing. Film analysts don’t necessarily agree.

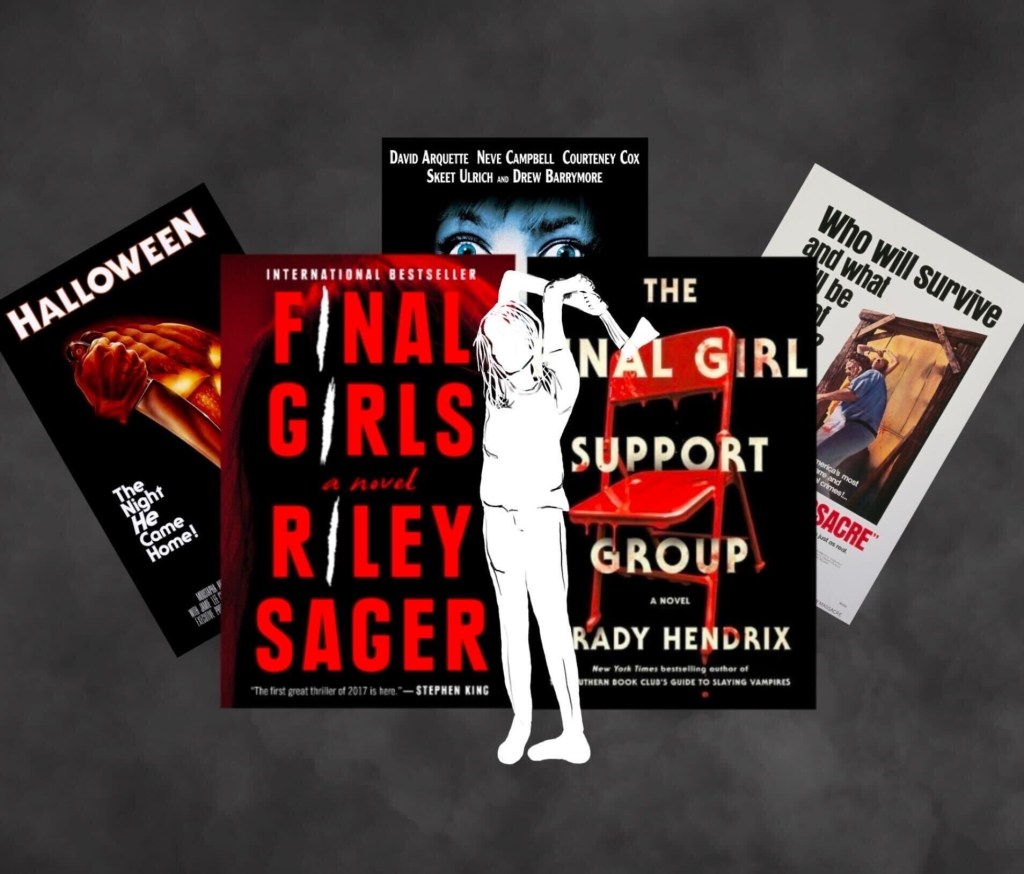

“The term “final girl” actually came about years after the release of classics such as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) and Halloween (1978) and was coined by UC Berkeley’s very own Professor Emerita Carol Clover.”

The term “final girl” actually came about years after the release of classics such as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) and Halloween (1978) and was coined by UC Berkeley’s very own Professor Emerita Carol Clover. In her horror analysis book, Men, Women, and Chain Saws Clover draws examples from a plethora of classic horror films (with an emphasis on the slasher subgenre) and breaks up the trope into a number of commonly observed factors. She goes in-depth into each facet of the trope; for the sake of effectiveness, we will confine the topic to the essentials. Academic and educator Caitlin Duffy has an excellent article on her blog that summarizes the first two essays of Clover’s book and brings in a few modern examples, something I will touch upon later. According to Clover, some of the fundamental factors that make up a final girl (and their respective film) are:

1. The sole survivor’s name (and demeanor) is usually “boyish,” such as the names Laurie or Ripley.

2. Since, as Clover argues, many slasher films are skewed towards a male audience and driven by male direction, the female victim is usually sexualized, yet characterized as innocent or sexually inexperienced.

3. As an audience, we are guided towards viewing the film from the perspective of the final girl, as per the characterization and camerawork that usually emerges in the second half of the film, a deviation from the first half’s “killer-driven” perspective.

Clover’s theory has remained plausible and is still applicable to a number of more recent slashers not analyzed in Men, Women, and Chain Saws. Modern media is laced with similar undertones of questionable directorial intent and perspective, and features important aspects studied by Clover. One example is X, (2022) in which, to summarize briefly, aspiring adult film star Maxine escapes a killer and her husband on a farm.

These aspects are prevalent in literature as well, most notably in The Final Girl Support Group by Grady Hendrix, which follows final girl Lynette Tarkington and a group of other female survivors that she meets with in hopes of finally moving on. One of the women in Lynette’s group is named Dani, which could fall under Clover’s name observance. Perhaps the most interesting and relevant feature of this book, however, is how it is revealed in Lynette’s backstory that she was a virgin the night that the killer struck. Lynette is characterized by the other final girls as a “fluke,” dragged by the media for rumors that she had a sexual relationship with the killer beforehand, so this detail seems like it’s supposed to come as a shock to the reader.

It’s hard to distinguish whether or not the inclusion of this plot point really is in support of Clover’s theory, in that male-directed media tends to fixate on the female character’s sexual status and how it affects her “purity” as a victim, or if it is an intentionally cliched detail. Hendrix possesses an impressive knowledge of classic horror, evident from his 2017 book, PAPERBACKS FROM HELL: The Twisted History of ’70s and ’80s Horror Fiction. Given that The Final Girl Support Group pays homage to a number of classic final girl films, it seems possible that Lynette’s characterization is meant to be a portrait of a cliched, male-driven heroine of sorts.

The Final Girl Support Group is one of many modern pieces of media that yields a plotline in which a group of women survive a traumatic event when they are young which they are forced to confront again when they are older. Of course, this could be a result of our formula-loving viewer tendencies, the same ones that endanger final girls like Sidney Prescott over and over again to churn out a profitable franchise. The book, Final Girls, by Riley Sager follows this same exact idea; three final girls, riddled with posttraumatic stress from their respective events, must confront their past once more. (Fun fact: Riley Sager is actually a pen name for Todd Ritter, who claims he wanted to choose a gender-neutral name to help establish a clean slate for his work.) Aside from just these two books, recent TV shows such as Yellowjackets, follow a group of women who survived a traumatic event and are forced to dredge up old memories. Countless TV shows and films such as Pretty Little Liars: Original Sin and Totally Killer (2023) reveal returning killers or trauma.

Standing by Clover’s extensive analysis of gender in film, it seems possible that this somewhat “new” trend could point towards a deeper, psychological urge to see a final girl suffer again and again. Without an updated sequel to Men, Women, and Chain Saws, however, these observances will have to remain just that. It is also interesting to note that there is a lack of female-directed slashers so there’s really no comparison to make, which complicates the question of whether or not we can spin final girl films as empowering.

“I can attest to the fact that this newfound awareness of the theory doesn’t minimize the trope’s nostalgia or viewing experience, but simply arms you with the ability to recognize the seemingly fortuitous, male-driven nature of the media.”

Perhaps next time you sit down at a theater, buttered popcorn in hand and blood-red Icee melting in the cup holder, you’ll be equipped with some basic knowledge of a final girl film’s recipe. I can attest to the fact that this newfound awareness of the theory doesn’t minimize the trope’s nostalgia or viewing experience, but simply arms you with the ability to recognize the seemingly fortuitous, male-driven nature of the media.

Leave a comment